This is the second part of a series on the recent incidents in AMU. You can read the first article here.

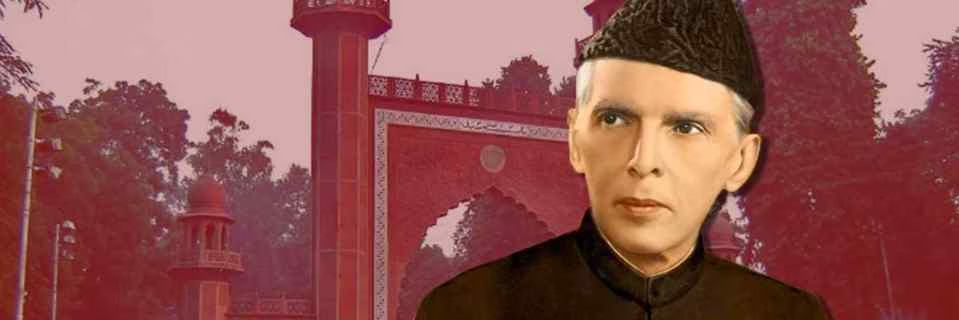

When a BJP MP recently asked Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) to explain why a portrait of Muhammad Ali Jinnah was hanging on campus, it should have been clear that the ground was being prepared for a confrontation. After all, the portrait has been on display in the students’ union hall since 1938.

As if on cue, right wing organisations loosely raised the issue. On Thursday, the situation escalated and led to clashes, with dozens students being injured.

It is now abundantly clear that the police played an extremely partisan role in the entirely avoidable controversy over the portrait of Jinnah, maybe because they are fully aware of the ideological position of their political masters. While the chief minister and several other ministers have spoken about the incident, they have not condemned the activists who created this crisis.

Why did the police allow Hindu Yuva Vahini’s activists to enter the university? Why were the troublemakers eventually released by the police? Why were peaceful student protestors lathi-charged?

Leaving aside questions of politics, the recent events in AMU should serve as an occasion for us to revisit our laws on crowd control. We continue to use repressive laws from the colonial era to disperse crowds. These laws were enacted by the British for their subjects. These laws have become dated with democracy and the right of citizens to demonstrate. The Supreme Court has held that government rules cannot prohibit even a government employee from participating in a demonstration. The right to assemble peacefully without arms is a fundamental right under Article 19(1) (b) of the constitution

Law enforcement agencies have to face two kinds of crowds – an orderly one and a disorderly one. Orderly crowds do not gather for agitation etc. but for entertainment at fairs, festivals, cultural performances, sport events and for social, political and religious purposes. Some demonstrations too can be peaceful and termed as orderly crowd (silent candle marches).

On the other hand, the disorderly crowd is an aggressive crowd willing to be led into lawlessness. Disorderly crowd may come into existence right from its inception where the motive of such an assembly is to create social discord to destabilise the society. The Hindu Yuva Vahini activists who entered AMU and raised provocative slogans were certainly a disorderly aggressive crowd. The police failed in its duty to restrain them.

Then, there may be a disorderly crowd which perhaps had gathered for a legitimate purpose soon turned into a violent mob. All the disorderly crowds fall under the category of either

- unlawful assembly,

- or riot.

Crowd control under the Indian Penal Code

Section 141 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 defines the unlawful assembly in following terms:

“An assembly of five or more persons is designated as unlawful assembly” if the common object of the persons composing that assembly is –

- To overawe by criminal force, or show of criminal force, the central or any state government or Parliament or the legislature of any state, or any public servant in the exercise of its lawful power of such public servant; or

- To resist the execution of any law or of any legal process; or

- To commit any mischief or criminal trespass, or other offence; or

- By means of criminal force or show of criminal force to any person to take or obtain possession of any property, or to deprive any person of the enjoyment of a right of way, or of the use of water or other incorporeal right of which he is in possession or enjoyment, or to enforce any right or supposed right; or

- By means of criminal force, or show of criminal force, to compel any person to do what he is not legally bound to do or to omit to do what he is entitled to do.

Explanation: An assembly which was not unlawful when it assembled may subsequently become an unlawful assembly.

The essence of the offence is the “common object” of the persons forming the assembly. Mere presence in an assembly does not make a person a member of an unlawful assembly unless it is shown that he had done something or omitted to do something which would make him a member of an unlawful assembly. The AMU protestors were simply asking the police to register an FIR and arrest people who allegedly trespassed into their university.

Section 146 of IPC defines the term ‘riot’ as follows:

“Whenever force or violence is used by an unlawful assembly or by any member thereof, in prosecution of common object of such assembly, every member of such assembly is guilty of the offence of rioting”.

In Emperor vs Raghunath Venaik Dhulekar, a procession of Hindus was about to pass in front of a mosque, which could have probably resulted in a riot. They were confronted by a police officer who ordered them to stop playing music and disperse. However, the leader of the procession did not obey the order and on the contrary, advanced a short distance while playing a drum. Subsequently, when the police resorted to a show of force, the procession laid down their musical instruments and dispersed. The leaders of the procession were charged guilty.

Section 153 provides for the punishment of a person who maliciously or recklessly provokes another by commiting an illegal act knowing that such provocation will incite others to rioting. Where some Muslims formed themselves into a procession, and proceeded along a certain route in disobedience of the orders of the Police Officer and came into contact with a procession of Hindus, they were held guilty of an offence under this section. (Gulam Kadar v. State AIR 1928 Bombay 156). AMU students were clearly provoked by the Hindu Yuva Vahini activists.

Section 153A punishes the doing of activities which promote enmity between different groups on the grounds of religion, race, language, caste or community etc. The gist of the offence is the intention to promote feelings of enmity or hatred between different classes of people.

Section 153-B (inserted in 1972) provides for the punishment of three types of communal propaganda:

- The imputation that any class of persons cannot by reason of they being members of any religious, racial, language or regional group or caste or community, bear true faith and allegiance to the constitution or uphold the sovereignty and integrity of India;

- The assertion that any class of persons by reason of their being members of any religious, racial, language or regional group or caste or community, be denied or deprived of their rights as citizens of India;

- Any assertion, counsel, plea appeal concerning their being members of any religious, racial, language or regional group or caste or community, and such plea or appeal causes or is likely to cause disharmony or feeling of enmity or hatred between such members and other persons.

Section 159 punishes affray i.e. when a fight between two or more persons on a public place lead to mob violence. It is hoped that peaceful protestors of AMU will not be attacked by the rival extremist groups who are openly threatening to yet again enter the university to forcibly remove Jinnah’s portrait.

Crowd control under Code of Criminal Procedure

Code of Criminal Procedure (Cr.PC) provides the machinery for the effective administration of substantive law. Section 129 of Cr.Pc empowers the executive magistrate or the police officers to command the unlawful assembly or the assembly of five or more persons likely to cause a disturbance of the public peace to disperse. In Karan Singh v. Hardayal Singh, the Punjab and Haryana High Court held that before any force can be used for the dispersal of the unlawful assembly, three conditions are to be satisfied:

- There should be an unlawful assembly with the object of committing violence or an assembly of five or more persons likely to cause a disturbance of the public peace.

- Such an assembly is ordered to be dispersed.

- Thirdly, in spite of such an order, the assembly does not disperse.

From video footage available, it seemed like the students had not assembled to create violence. It is not clear how far police followed these guidelines in dispersing students of AMU. If they really indulged in violence, police may have a case. Why police did not use water cannons remains unexplained. But the police have been brutal when it comes to dealing with students in other universities as well. In BHU, even women students were not spared in 2017. Similar was the case with JNU protesters who were lathi-charged only March 30,2018. Osmania students too were lathi-charged in 2017. On March 30 this year, CBSE and SSC students too were lathi-charged. Thus, let us not give a communal colour to police in the AMU case. The fact is that our police is ill-trained in dealing with crowd control.

The law on crowd control is very clear. As far as possible, only minimum force should be used in dispersing the assembly. If any such assembly cannot be otherwise dispersed and if it is necessary for the public security that it should be dispersed, the executive magistrate of the highest rank who is present may cause it to be dispersed by the armed forces under Section 130.

The most important provision which is commonly used to control the crowd is Section 144. The Section confers powers to issue an order in urgent cases of nuisance or apprehended danger.

The order may direct:

- Any person to abstain from a certain act, or

- To take certain order with respect to certain property in his possession or under his management.

The grounds for making the order are that, in the opinion of the Magistrate, such a direction is likely to prevent, or tends to prevent obstruction (b)annoyance, or (c) injury to any person lawfully employed , or (d) danger to human life, health or safety or (e) a disturbance of the public tranquility, or (f) a not or (g) an affray.

No shoot at sight orders

An order under Section 144 must be clear and definite. The executive direction contained in the “Important Announcement” issued by the state government, in so far as it held out to be the members of the public the threat that a curfew breaker for the mere breach of the curfew would be liable to be shot at, was held by the Gujarat high court as ultra vires the executive powers of the state government and also ultra vires Section 144 of Cr.P.C. Section 188 of the IPC and Article 21 of the constitution. (Jayantilal v. Eric Rension)

Crowd control under Police Act

The Police Act of 1861 has conferred various powers on the police to deal with the problem of crowds. They can regulate public assemblies and processions and while doing so can impose conditions of license. Section 30 of the Police Act gives the police the power of control processions. Police is authorised in certain circumstances to require persons to apply for the license. The object of this provision is that adequate arrangements for the crowd control are made in time. Clause (3) of Section 30 gives the police power to define the conditions on which a procession shall be permitted to take place. If any of such conditions are broken, it is an offence punishable under Section 32. Similarly, if there is a failure to apply for license, there is violation of an order issued under Section 30. But police have not been given the power to forbid the issue of a license for a procession. Here power to control does not include power to forbid.

Section 30(a) of the Police Act empowers any magistrate or district superintendent or assistant superintendent of police or any police officer in charge of a station to stop any procession which violates the conditions of the license and to order it to disperse. Any person who refuses to disperse on such an order would be liable, regardless of his awareness about the conditions of the license. The liability in such a case would be of a person who neglects or refuses to disperse and he would be deemed to be a member of an unlawful assembly as punishable under Section 143 of IPC.

Thus the Police Act has conferred vast powers on the police to control processions and assemblies but they are expected to exercise these powers in such a way as not to unnecessarily jeopardise individual freedoms which are all important for successful democracies.

AMU students can legitimately protest in a peaceful manner against the discriminatory attitude of the police if they feel that police was soft on the Hindu Yuva Vahini but harsh on them.

But then it is the responsibility of protestors to ensure that protests remain fully peaceful. They should refrain from unnecessarily attacking senior district administrative and officers. Similarly, the government should not be criticised for the actions of non-state actors. It can of course be attacked in a decent and civilised manner for protecting aggressors and not taking action against such non state actors. If any student has broken the law, he too is to be condemned.

The mere fact that policemen too have been injured indicates that as police started to lathi-charge, few undesirable elements (outsiders or ex-students) may have taken advantage of the ugly situation. Accordingly, an FIR has been filed against them. Ideally, police should first arrest the initiators of trouble who unnecessarily trespassed into university premises and provoked AMU students.

Saturday’s Amar Ujala has reported that student protestors attacked an independent photographer associated with a local BJP leader and that he was saved by the AMU proctorial bulls (i.e. security staff) who “had no option but to open fire”. This author was shocked to read of this as such behaviour is against AMU’s tradition. However, the authenticity of this news item needs to be confirmed since bulls are not given arms and perhaps the allegation is merely another effort to tarnish the image of AMU’s students.

It seems that the government has already ordered magisterial enquiry into the incident and therefore students should now call off their strike and go back to studies. They should save their academic year. University administration, teachers, staff, their seniors and above all Hindu liberals and human rights defenders will surely fight on their behalf. They should have faith in country’s legal system and constitution.

The problem of crowd control should not be treated merely as a law and order problem because it involves numerous social, political, religious and cultural considerations. The law confers enormous powers upon the police to manage all forms of gatherings which take place openly and in a clandestine manner. But then, the police should be extremely cautious and discreet in the use of force because these powers of the police must not infringe constitutionally guaranteed freedoms of the citizen such as free speech and right to protest.

If the police are to function as impartial agents of law, their professional independence from unauthorised interference should be deemed as sacrosanct as the independence of judiciary. Let our police be liberated from political control. Let salaries, perks and service conditions of lower police officials be improved to bring in them much needed humility. Let us appreciate that our police constables have long hours of duty and get very little sleep. They do not get enough chances to visit their families. Let us understand that police officials work in extremely harsh and demanding situations. They too are human beings, who like us, are fallible.

Faizan Mustafa is vice-chancellor, NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad. The views expressed are personal.